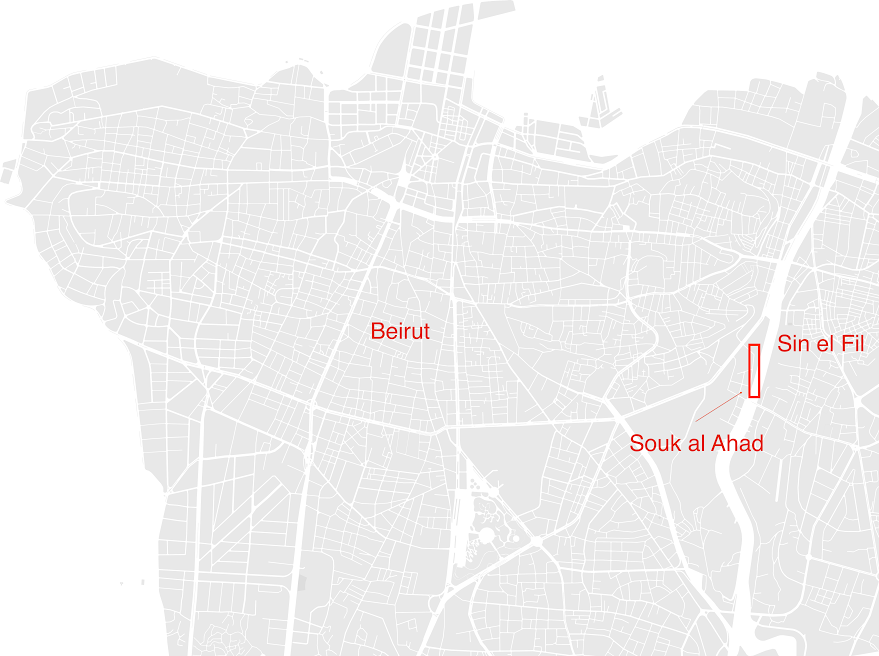

Beirut’s weekend market Souk al-Ahad attracts about thirty-five thousand visitors a day and has four hundred registered stalls, providing a living to five thousand families. It is located on the eastern edge of the city near its river and a highway (Figure 1). Beyond the physical collection of stalls, vendors, and affordable goods, the Souk is also the locus of a long conflict over land ownership between the Lebanese Ministry of Energy and Water and the municipality of neighboring Sin el-Fil. In the case of Souk al-Ahad, “the state” that designates what is legal or illegal is not a unified front. Rather, two public bodies belonging to the state employ the designation of a space as legal or illegal as a tool to advance their own interests. In turn, just because the actors are related to “the state”, their interests cannot simply be termed “public.”

[Figure 1: Map of Beirut showing the location of the Souk.

Source: Map by M.Krijnen, based on the 2006 map of the Directorate of Geographic Affairs of the Lebanese Army.]

As we will show, there are significant private interests at stake in the conflict, as well as various struggles over the very meaning and limits of what/who constitutes “the public.” These interests include: i) the connection between the private actors exploiting the Souk, and the minister who licensed them to exploit this public land; ii) racist and nationalist concerns about Syrian refugees; and iii) possible interest in the land because of nearby real estate developments that have led to skyrocketing prices of land. (This last factor is not confirmed, but is expected given the many connections between real estate developers and politicians. See also here). Literature on urban informality has observed that the state’s power to designate what is legal or illegal often functions as a tool for the management of urban space.[1] The (il)legality—and its counterpart: (in)formality—of urban spaces is thus seen not as an inherent, absolute quality but rather a flexible tool that can be employed to serve the state’s interests. Our story complicates the narrative of homogeneous public state actors using legal/illegal designations as instruments of urban management, and also questions an understanding of state-owned, non-buildable land as supposedly serving the public good.

Moreover, our story will shed light on divisions existing within the Souk itself, moving away from simplistic representations of the market as a homogeneous collective space. Social divisions amongst the vendors have become far more acute since the influx of Syrian refugees over the past three years, with one group of vendors accusing another of being “illegal” and “foreign.” This phenomenon adds a layer of social conflict to a space whose legal foundations are already contested, thus further complicating the dispute. Many of our interviewees spoke of the existence of two separate overlapping interlocking markets within the Souk, divided by the claimed legal status and social identities (and type of goods and prices) of their vendors. This article will explore the relationships between these two markets, and explain why the Souk’s exploiters, vendors and state actors perceive them as separate entities.

Through this analysis, we aim to complicate media reports that consistently portray the Souk as a homogeneous space, where mostly undesirable members of the public gather to engage in illegal activities, a crowded health hazard “swelling” with vendors selling a variety of (often illegal) goods to the “heaving” masses, and “suffocating traffic” of lower income families, accompanied by all varieties of stenches. One recent TV-report portrayed the market as being a space “outside the law in the heart of the capital.” The Souk’s visitors are accused of blocking the entrances to Beirut, throwing garbage in the river and being loud. In short, the Souk is “in crisis.” At the same time, so-called “educated and affluent” people (along with both local and foreign breeds of hipster) come for the rare books and antiques, and some media reports in this vein highlight the “multi-national” character of the market. The romanticized and stigmatized portrayals of the Souk prove to be overly simplistic in light of our findings, and gloss over competing claims of legality and legitimacy that exist both outside the Souk, in the form of the conflict over land ownership between the Ministry of Energy and Water and the municipality of Sin el-Fil, as well as inside it, in the form of social divisions based on claims of legality and nationality. This article aims to explore this complexity.

[Figure 2: Souk al-Ahad. Picture taken on 7 December 2013 by R.Pelgrim]

The article is based on interviews conducted by the authors at the Souk in Beirut in December 2013 (with additional interviews by Richard in February 2014), a review of relevant laws and decrees, as well as about two-dozen court cases, and other legal documents related to the ownership dispute, stretching over three decades. We also conducted an online search for sources in English, French and Arabic.

Souk al-Ahad: A Background

Souk al-Ahad’s story begins just after the end of the Lebanese civil war in the early 1990s, when a group of vendors began to gather regularly on a vacant plot of land near the Beirut River. The spot was conveniently located near major urban commercial centers such as Achrafieh and Bourj Hammoud, and easily accessible from other areas within Beirut (Figure 1). Over the years, the market, which at that time was unlicensed, grew and began to attract more and more vendors, and customers, mostly from lower social classes. Slowly, various forms of organization, hierarchy, and regulation emerged, and small rental fees were charged in order to provide electricity and maintenance. This trend developed until the Chedid and Irani families gained the upper hand. In 1996, they managed to strike a deal with then-minister of Energy and Water, Elias Hobeika (assassinated in 2002), with whom they were connected politically. The exact details of this connection remain unknown. Neither the tens of official documents concerning the plot and its ownership, nor the representatives of the Chedid and Irani families revealed much more information than this. The narrative of the families’ rising influence remains vague, the (important) details lost in the complexity of conflicting official records and word-of-mouth stories. What is clear, however, is that since the land is amlāk nahriyya (river property) based on decree 144/S-1924, and thus belonged to the ministry, minister Hobeika argued that he had the right to lease the land for private use, based on a decision from 1981 by the same ministry, allowing investment companies to occupy river lands (decision 7/1/1981, and a similar decision in 1974). Through this deal, the market was given a legal status by the ministry, and Chedid and Irani were guaranteed their right to exploit the market.

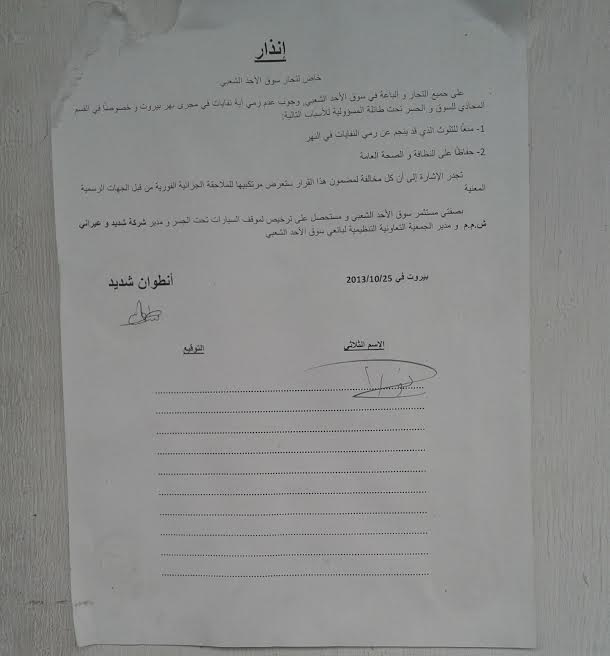

The lease of the land to Chedid and Irani meant more structure and regulation in the workings of the market, with the market’s operators also increasingly intervening in disputes, and daily matters of cleanliness and maintenance (Figure 3). The lease also gave Chedid and Irani the right to charge rental fees to the vendors. The current Souk is thus not a “mere” agglomeration of unregulated, informal vendors, but is in fact a legal and structured business, with each stall inside the Souk registered, and paying rental fees to the legally-sanctioned investors/exploiters of the plot. Guesses and estimates concerning the exact rental fees per stall vary. Most recent newspaper articles cite a fee of 10,000 LL (6.5 dollars) per sq.m per month, in which case the operators would make around 45,000 dollars per month.[2] The operators themselves deny they charge this much, and vendors consistently contradict each other on these numbers, citing weekly rental fees varying from 60,000 LL (40 dollars) to 15,000 LL (10 dollars). One vendor said: “It goes up to one million LL (667 dollars) per two days for really big places, but you also have 10,000 LL (6.5 dollars) stands.”

[Figure 3: Notice at the market. Picture taken on 7 December 2013 by R.Pelgrim]

Contested Legality: The Souk’s Land Ownership Dispute

It is tempting here to write a story about greedy “landlords” who charge exorbitant rental fees from poor vendors. While this is definitely the case, doing so would exclude a number of vital nuances in the relationships between the various actors. To begin with, we met a number of vendors who had much praise for the Chedid and Irani families: “Chedid is a great guy. If you can’t pay one week, it’s OK. He takes good care of us. They provide us with a place to work and make a living.” Beyond that, however, the picture gets particularly interesting and complicated, as we consider the fact that the legality of Chedid and Irani’s lease of the land has been put into question repeatedly by the municipality of Sin el-Fil, on the other side of the river.

The definition of legality in the case of the Souk is highly contested. Two state agencies, the Ministry of Energy and Water and the municipality of Sin el-Fil, are at odds in this dispute. Yet, each side relies on legal arguments and documents to prove their cases, and has appealed to court to obtain their perceived rights. “The state,” just like “the Souk,” is rife with internal fissures and contradictory forces. The municipality claims ownership of the land on which Souk al-Ahad stands and possess a property title to prove it: a cadastral record of plot 2505/Sin el-Fil indeed states their ownership since they claimed it in 1993. The mayor of Sin el-Fil argues that the lease given to Chedid and Irani in 1996 was, first of all, a one-year lease that has never been extended, and, second, that a minister cannot decide to lease state property for private investment unless the council of ministers approves this decision.

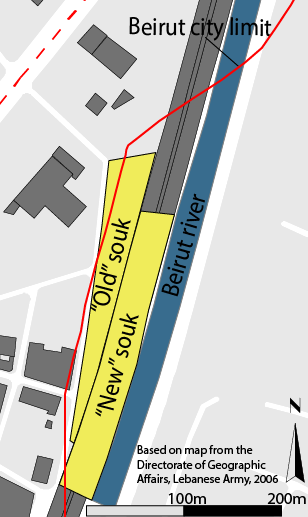

As recognized by local residents, the Beirut River marks the eastern city limits. Therefore, Sin el-Fil’s ownership claim may seem a little strange at first sight, since Sin el-Fil and the Souk are clearly on opposite sides of the river. However, the municipality’s argument can be related to the alteration of the river’s path (and the concretization of its boundaries) in 1968, which led to the annexation (or appropriation) of a large field of river domain to Beirut, resulting in Sin el-Fil’s street grid ending abruptly at the river’s walls. According to the municipality, this project left parts of the land (specifically that on which Souk al-Ahad stands) on the “wrong” side of the river.

However, the Ministry of Energy and Water says that the municipality’s record of ownership is illegal. The minister states that ownership never should have been transferred to Sin el-Fil in 1993, and refers in a court document to the “mysterious way” in which the municipality obtained the property title without the ministry’s knowledge (26/S, 24/2/2007). In our interviews, various vendors and people in charge of the Souk shared this view. The mayor of Sin el-Fil argues that this accusation has never been properly investigated, that the market’s operators used to be protected by the Syrian secret services, and today, “God only knows who supports them”. Our review of court documents and decisions issued by the Ministry of Energy and Water between 1993 and 2012 shows that the ministry has consistently supported Chedid and Irani. The minister argues that the lease conditions postulate an implicit yearly renewal of the lease, and emphasizes repeatedly that the land is public river property, and should never have been transferred to Sin el-Fil in the first place.

In 2007, Beirut’s Court of First Instance ruled in favor of the municipality, and issued a verdict of eviction. The ministry appealed right away, as they saw the verdict against Chedid and Irani as an infringement on their state rights. A new verdict was not forthcoming at the time of writing, to the dismay of the mayor of Sin el-Fil. At present, the mayor is hoping for the Council of State to rule on the case, and negotiating to move the Souk to the area of Karantina, located in the northeast of the city in in the industrial area of Medawar. He plans to convert the riverside land into a public garden. It has already been noted that the area in which Souk al-Ahad is located is undergoing significant and rapid real estate development and gentrification, with land prices quickly reaching 7,000 dollars per square meter. The Souk covers around 9,300 sq.m of land (according to court and cadastral documents we consulted). The ministry, meanwhile, keeps on urging the court to take action, complaining that Sin el-Fil municipality is encroaching on their lands (not only Souk al-Ahad), and expressing their wish to sue the municipality for their “criminal actions” (document 6424 or 357/S, 18/10/2012, and many similar documents from the mid-1990s onward). They complain about “the renewal of the encroachments of the municipality and its arrogant transformations on every plot in this neighborhood at the expense of the laws and high national interests.” It is not clear which encroachments they mean exactly as this is not specified, but it is clear that the municipality has not constructed anything in the Souk area itself.

When asked about the dispute, vendors confirmed what we have heard. However, opinions varied on whether the Souk’s operators had won the case already, with some claiming that they had obtained a ninety-nine-year lease. The general agreement was clearly that the land did not belong to Sin el-Fil but to the Ministry of Energy and Water. When asked whether they thought the Souk was in any danger of eviction or relocation, especially considering the increasing criticism and stigmatization in local media, no one seemed to be too concerned. “No, everything here is legal and on paper. We have the right to be here,” one vendor told us.

During our interviews, Chedid and Irani’s representatives did mention the increasing number of residents` complaints, which may be playing into the hands of the Sin el-Fil Municipality in their attempt to claim the land and evict the market. We found Chedid’s representative and his son sitting in an upscale antique store at the end of the Souk, and began to ask a few questions concerning the ownership dispute. When the representative saw the maps we had with us, which included the zoning boundaries of Beirut, he became very nervous and defensive. He asked us for identification papers and the purpose of our research. It seems that the owners of the Souk are, at least in some ways, still quite nervous about the conflict surrounding the ownership of the land. The simple narrative of greedy, all-powerful landowners becomes more complicated, as they also experience certain forms of vulnerabilities and possibilities of loss. Clearly, the power they wield over the far more vulnerable vendors is not without its own instabilities and risks.

The discourses and arguments made on each side of the river mobilize various moral “truths” in order to win over public opinion. In an interview with Al-Afkar, the mayor of Sin el-Fil repeatedly claims to be concerned primarily about traffic congestion, public and environmental health, and the impacts on the residents of his municipality in terms of noise and security: “the nuisance, traffic congestion, throwing and burning of trash inside the river, and all other sorts of negative effects on the health of the citizen.” Another complaint is that many vendors are not Lebanese, which in this context means usually Syrian and other non-white foreigners. Chedid, on the other hand, highlights the importance of Souk al-Ahad as a place where lower-income families can find affordable items and make a living selling those items. He also emphasizes that the majority of his licensed vendors are in fact Lebanese. A salesman told us: “On the radio people are complaining that it’s dirty, but they should think a bit more before they say such things, because this souk serves thousands of families who can make a living this way.” Competing discourses, appealing to various notions of “legality” and “serving the public good,” are thus mobilized in the two sides’ efforts to claim legitimate ownership. In doing so, both sides envision a different public that deserves to be served, and that is viewed as having the right to the space, while in fact, possible motives of personal gain and private connections remain hidden.

The “Other” Market

[Figure 4: The “old” and “new” Souks as situated near the river and Beirut city limits. Note that the city limits shown here do not correspond with those shown on most maps, which take the river as the limit. We followed the Lebanese Army’s border in this case, showing that the city limit indeed excludes most of the Souk. Map by M.Krijnen]

Both the operators of the Souk and the Sin el-Fil municipality seem to agree on one thing: there is an undesirable, “illegal” expansion of the market. As mentioned earlier, there is talk of the existence of two separate markets within Souk al-Ahad. Walking through the market, you might very well not notice the difference. The older part of the Souk is organized in a grid pattern of stalls covered in white plastic sheets, and a newer section under the highway consists mostly of mats on the ground. Walking through this “new” part of the market, one experiences it as an extension, an almost expected growth of the Souk. Even though a small-scale addition has existed for years, recently it has expanded enormously due to the vast number of Syrian refugees that have entered the country over the last three years.

.jpg)

[Figure 5: The “new” part of the souk. Picture taken on 7 December 2013 by R.Pelgrim]

Vendors in the “old” part of the Souk (at least in their view of things) talk about the “extension” as qualitatively different, as a separate market, marked as such most powerfully by its legal and social status. They say the people “under the highway” are mostly Syrian refugees who have driven up the rental fees and prices. The goods sold there are cheaper, because they are mostly second-hand, and, as some disgruntled vendors from “inside” say, “taken from the garbage”. A pair of shoes costs as little as 5,000 LL (3.5 dollars), compared to 20,000 LL (10.5 dollars) or higher, “inside.” As one vendor, who has been part of the Souk since its beginnings, said: “It used to be worth it, but since the other market, it’s not anymore. As Lebanese, we have a lot more expenses than those people… we have a family, school fees, taxes and so on.” Chedid did not seem too worried about any potential competition from the new market emerging under the highway bridge, however. We did not see any empty stalls inside Chedid and Irani’s market. At least on the level of their income, the owners of the Souk have little to worry about.

Both operators and vendors of the “old” souk emphasize the illegality of the other part, compounded by it not being Lebanese; interestingly, the local media portray the entire Souk as being mostly foreign. As Chedid’s representative stated: “This part is legal. The red and white fence, the large arched sign—all are legalizing elements. It’s on paper. We will never move, but they, under the bridge, that’s a different story, they can be removed.” The market manager, Mohammed Sbeiti, told us: “Here, we have a permit for the stall holders, they are registered. The other market won’t last, it’s the refugees, and it’s possible to get rid of it.” A vendor said: “Under the bridge it’s not official, that part is from the municipality of Sin el-Fil.” And another: “Who knows. There is a big chance they will be evicted soon… There are rumors.” Hence, there is widespread agreement on the illegal status of the market outside the older Souk area, supported by increasing resentment towards Syrian refugees that can be found all over Lebanon.

This racist discourse conspires against foreign vendors and visitors at the Souk, and is used by the Souk’s management as well as the municipality of Sin el-Fil to argue their respective cases, albeit with a different outcome in mind. Chedid uses it as a contrast to his own legal status, while the municipality uses it as a reason to get rid of the Souk altogether because it bothers its residents. Hence, the “new” part of the Souk epitomizes Yiftachel’s “grey space:” they are not evicted, but they are also not part of the claims of legality of each opposing side.[3]

[Figure 6: The entrance to the Souk. Picture taken on 7 December 2013 by R.Pelgrim]

Interviews conducted in the “new” part of the market complicate Chedid’s claim of its illegality. We encountered a few vendors who had recently moved there from the “old market” because they could no longer afford the rent “inside.” Some claimed to be paying rent to the same owner as before, while others said they are paying it to someone else: “I pay 400,000 LL (267 dollars) for a double stall per weekend to Abou Jaafar. I don’t know if the same people run both Souks.” Another said he pays 200,000 LL (134 dollars) for a 4x5m stall per weekend to Chedid, and that the spaces are divided among the committee that runs the Souk. A third vendor said that he pays one hundred dollars for a 4x4 stall per weekend, and that there is only one operator for the entire Souk. Most were unwilling to talk, however, which is understandable given their vulnerable social position. There is obvious ambiguity as to the party actually claiming rent from the vendors, and to the seriousness of the management of the “old” Souk about getting rid of them. The vendors that did speak to us showed no concern about being removed anytime soon. As one said, leaning up against a two-meter-wide concrete column that supported the highway above us, a big grin on his face: “Do I think we’ll be removed…? Do you see this column behind me? This column will be removed before we are.”

Conclusion: Against an Oversimplification of Legality in Lebanon

As we have seen, in the case of Souk al-Ahad, what is designated as legal/illegal (and, therefore, formal/informal) is not clear-cut or agreed upon by state actors. Our findings therefore challenge any binary division between legal and illegal, and complicate the notion of a unified state that uses the designation of space as legal or illegal as a tool of urban management.[4] Instead, through our findings the Souk emerges as a stake in a legal (and social/moral) battle between state actors that are both trying to advance their interests by designating the other’s claims as valid or invalid. The perceived (il)legality of the vendors and space of the Souk by the ministry on the one side, and the municipality of Sin el-Fil on the other side, as well as its perceived and practiced (but also contested) division into two parts, show how claims from within and outside the Souk complicate a simple binary interpretation of this complex space. According to the municipality of Sin el-Fil, the Souk attracts undesirable people, presents a health hazard, and is proven illegal by documents in their possession. The ministry and the Souk’s operators, on the other hand, possess documents stating that the Souk is legal, and argue that the only undesirable public is the extended “new” Souk. Furthermore, owners, vendors, and media reports use racist and nationalist arguments to designate people and spaces as illegal and undesirable.

In the case of the Souk, the ministry and the municipality, two government agencies that can be considered to represent “the state,” are struggling in court to gain the upper hand for what they both claim to be the “public good.” However, true motives probably reside elsewhere. First, in the political connection between the Souk’s exploiters and the ministry, where then-minister Hobeika probably did his old ally from the civil war a favor by granting him a lease to exploit the Souk. Second, in the enormous profits made through the operation of the market, where rental fees charged from vendors might flow to the ministry one way or another. Third, in the xenophobia and middle class contempt for the poor from the side of Sin el-Fil municipality. Finally, in the potentially high revenue of the land if sold to a real estate developer, or if exploited by the municipality for other ends due to the skyrocketing prices of land of the gentrifying area next-door. The lines between the “public” and the “private,” and between the “informal” and the “formal” are blurry and fluid, changing in response to the interests of the various authorities involved. The case of Souk al-Ahad is not alone in this regard. With other similar developments, such as the forced relocation of street vendors in Saïda, and mayor of Beirut Bilal Hamad’s proposal to do the same in Beirut, thereby making all street vending of fruit and vegetables illegal, there is definite cause for concern for Lebanon’s lower-income classes. Any research on land claims in Beirut and Lebanon, however, should not assume the homogeneity or authority of “the state” in designating things as legal or illegal. Rather, new scholarship should pay attention to competing claims from discrete state bodies, and the complex mix of public and private interests, and stakes behind them.

[Both authors contributed equally to the article, hence their names appear in alphabetical order.]

[1] Ananya Roy, “Why India Cannot Plan Its Cities: Informality, Insurgence and the Idiom of Urbanization,” Planning Theory 8, no.1 (2009), 76-87.

[2] The plot on which the Souk takes place has an area of approximately 9,300 sq.m. Accounting for pedestrian passages and other unexploited space, an estimated 7,000 sq.m. remains to be filled by stalls.

[3] Oren Yiftachel, “Theoretical Notes on “Gray Cities”: The Coming of Urban Apartheid?” Planning Theory 8, no. 1 (2009), 88-100.

[4] Ryan T. Devlin, “‘An Area that Governs Itself’: Informality, Uncertainty, and the Management of Street Vending in New York City,” Planning Theory 10, no. 1 (2011), 53-65; Ananya Roy, “Strangely Familiar: Planning and the Worlds of Insurgence and Informality,” Planning Theory 8, no.1 (2009), 7-11.